Foresights and ideas that expand minds and inspire a change of heart.

The sense of place can be both a gift and a curse. The location which sits at the core of provenance marketing is a double-edged sword. Only Champagne from Champagne can be legally called Champagne. Chicken Bega doesn't have the same ring to it as Chicken Parmiggiano, and Yunnanese Pork doesn't whet one's appetite the way apple-smoked Canadian bacon does. A region has either built a world class reputation for a particular produce, brand equity in its provenance, and trust in its sourcing practices, or it hasn't.

It bolsters businesses in the sense that they can tap into the brand equity of the region, but the regulation associated with the intellectual property of place can also hamper innovation and development. On the flipside, for regions like the Languedoc-Rossillon, the sense of confused identity and provenance in this lesser known wine-growing region of France, offers both opportunity and challenges as local winegrowers are seeking to unshackle themselves from commoditised brand associations, and enter the imaginations of global foodies whose sense of French geography is limited at best.

These are regions blessed with history, famous landscape paintings, and a tradition for artisan and local craft - importantly they have made a name for themselves globally, as great local French brands. While these areas have entertained the up-market aspirations and status anxiety of consumers around the world for decades, if not centuries, the Languedoc-Rossillon, has not been able to create the same kind of brand equity. Yet it seemingly is desperate to re-create the successes of its neighbours, even if it is at the expense of its legal name, Languedoc-Rossillon, in favour of the more internationally sounding Sud de France. In a gesture toward identity conflict, certain lobby groups wish to let go off the poor brand associations of the Languedoc-Rossillon as the major contributor to the French wine glut, in order to start afresh, by tapping into what the world knows, or think it knows, about the south of France and the Riviera. These types of lobby groups, supported by the region's elite business families realise that location and how it is communicated in business is absolutely critical for a sub-brand that belongs to the region and tries to navigate its way through the regulatory maze, created largely to protect the local growers from international competition.

Having grown up Swedish, but having spent a lot of my time in the Anglosaxon world, I am still aghast at how many times people associate chocolates, watches and Roger Federer with my home nation. There are ostensibly two times in the year when non-French natives might care about French geography - one, if they are planning a holiday in France, and two during the Tour de France, when we are bombarded on television with the names of French villages, and maps of the various stages of the tour. Yet, the wine brands and dynasties insist on marketing place, terroir and AOP, as their key asset, to a consumer who doesn't know where the Languedoc-Rossillon is, doesn't understand the amorphous term 'terroir', and couldn't care less for French protectionism dressed up as unique provenance marketing.

Whether the consumer is always right is another matter, and one wishes perhaps that people were generally more interested in geography, and the provenance of produce beyond the mainstream regions of the world that we all know about. Add to this confusion, perhaps based in part on the French conviction that they are well placed to educate the world about wines, the fact that most consumers base their wine choices on grape varietal, rather than on a deep-seated trust of the chemical properties of the soil in an unknown region somewhere between the Alps and the Pyrenees, and you have the perfect recipe for consumer lack of savoir faire. To the chagrin of the French wine producer who loves his soil, and who cannot fathom why the world doesn't understand the value of his unique terroir.

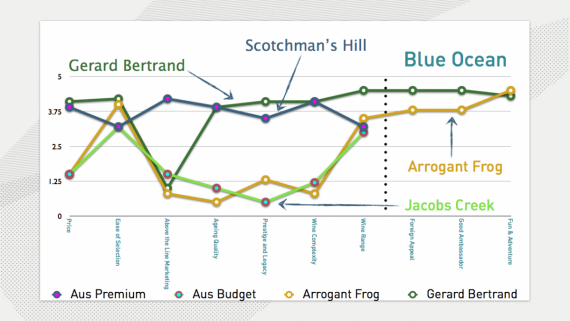

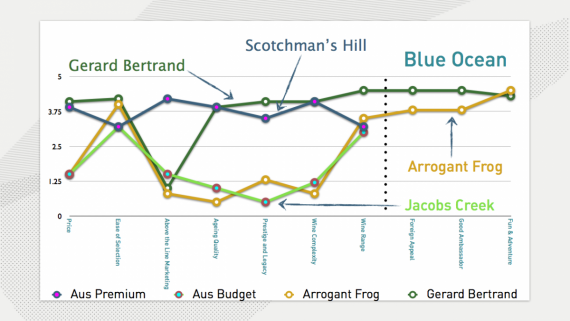

This focus on the local is perhaps not surprising of the old world. It showcases the tension and dynamic in their competition with the new world, which has been somewhat more free from the regulatory and traditional burdens of place. I mean, Argentina, Australia, California, and New Zealand had to earn a reputation in a global wine economy that hadn't grown used to respecting the provenance of Mendoza, the Barossa, Napa Valley, or the Marlbororugh. If you used small scale place and location as the starting point for marketing Australian wines in the US, where the consumer knowledge of Australian geography is limited at best, and the wine consumer at large would be considered unsophisticated at best by international wine snobs, you would most likely struggle in your provenance marketing efforts. If, however, you went to market in a way that demystified wines, focussed on fun labelling, zoomed out and associated the brand with the nation continent of Australia rather than a micro-climatic terroir, and went to market with a quirky point-of-sale focussed campaign, you might do well. While this Yellow Tail example of a Blue Ocean Strategy is an interesting case in point of splitting with the traditions and competitive dimensions accepted by an industry, the larger lesson is that it focussed on the consumer first and foremost, something the French wine industry would do well to adopt. Having spent a couple of weeks in the south of France and working with a family business, I understand that this is not always easy. The shackles of tradition, passing on a legacy, and fierce local, dynastic rivalries sometimes takes precedence over commercial nouse, and places cognitive barriers around what is possible. The AOP regulatory frameworks further stifles innovation, and becomes an easy mental prison, and an excuse not to market wines in a more user-friendly fashion.

It is perhaps illustrative that the French equivalent to the Yellow Tail example above, is an innovative effort to market old world wines to the new world. Taking on the new world at their own game as it were. The strategy used by Jean-Claude Mas' Arrogant Frog in its Australian and US marketing could be considered a duplicate of Yellow Tail's American go-to-market strategy, but has been hugely successful in Australia at 1 million bottles sold each year. Jean-Claude Mas' stroke of insight came from the anti-French sentiment from the early 2000s when President Bush called the French 'arrogant frogs', and used this consumer insight into the minds of (some) Americans to brand a product line which could be accepted by the consumer, and interestintly appealed to the Australian perception of the French as well.

Interestingly, this line of wines is significantly differently branded than the main family of Mas labels to avoid brand confusion, and perhaps to avoid local French jealousies for his innovation in communicating the varietal and the brand identity, rather than the terroir and the appellation. The example is illustrative of the type of commercial success that is possible when you empathise with a consumer who is bombarded with jargon, snobbism, micro-climate information, and often doesn't even check out the back label, which the wine industry considers such a huge communication opportunity. At times, while I was in France, you got a sense that many producers suffered a kind of artist's dilemma, where commercial success was akin to selling out, and many accepted 'foreign currency' instead of cash. In other words, write ups, article features in industry magazine, critical acclaim, local respect, and toiling the soil are sometimes substitutes for commercial success and revenue. Lifestyle, tradition, and terroir come in the way of innovation, consumer awareness, and channel marketing.

This is where provenance marketing, as I experienced in the Languedoc-Rossillon, falls short. Most winebrands in the region fail to meet the consumer half-way. They communicate the same way, in the same order and sequence, and trust that the quality of their grape juice will be noticed by the consumer. Industry trends and consumer awareness, partly driven by the internet, digitisation and mobilisation of content should all favour local story telling.

Foodie trends like 'farm-to-table', locavorism (the global word of the year in 2007), artisanship, story food, reality tv food shows, source and traceability should all buoy tradition and the local. If done right. However, the French wine industry, as a whole has been slow to respond to consumer appetites for information. Focus has been on telling a story in the analogue world on their bottles, labels, and images of chateaus, and less on helping the consumer make sense of the context of the bottle of the shelf. The branding messages get lost in the level of abstraction, at which the message is pitched. While the consumer might be thinking 1. Shiraz (varietal) with my beef 2. Price Bracket (for the occasion) 3. General Region, they rarely even consider the location or micro-climate at the point of sale. The level of abstraction at which they are operating is too high for the terroir focussed wine producer who fails to capture any mindshare, given that the order they communicate in is 1. AOP to indicate micro-climate terroir 2. Chateau Location Name 3. Blend of varietals determined by the appellation regulations. The consumer is lost. A better context or level of abstraction would be to get in line with consumer thinking, and provide valuable contexts at each level of abstraction which positions the wine favourably in the minds of the consumer. For example in Australia - 1. Syrah (awesome for your BBQ) 2. Top of the pops of our wines [made affordable by the strong Australian dollar] 3. Sud de France 4. Link the region back to something Australians know like Tour de France personalities and 5. Incorporate digital / mobile story telling and video so that the consumer can attain status by telling their mates about a great wine they found and shared via their digital and analogue networks.

On reflection, there is a great shame that regulation, sophistication, and tradition stands in the way of commercial success. Seemingly intelligent people are not always commercially savvy, and this region is a case in point. If I ponder the future for the region, and others like it, I imagine that the agricultural land might find a different use than wine growing in the future. Wine is a luxury, and on a global scale where we have a wine glut, but a food shortage, and with 2 more billion people entering the global food market over the next 35 years, traditions and lifestyles will increasingly come under pressure, as there will be new demands on the productivity of the terroir. Despite government protectionism, it is unlikely that many producers will be able to tell the stories of their terroir in 10, 20 or 30 years, unless they change how they communicate and brand their produce in a way that captures the hearts and minds of a local, regional, national and international market.

Header Text

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Header Text

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Header Text

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

& STAY UP TO DATE WITH FORESIGHTS AND TREND REPORTS!

WE WILL EQUIP YOU WITH THE VIDEOS AND MATERIALS YOU NEED TO SUCCESSFULLY PITCH ASN.

0 Comment