Foresights and ideas that expand minds and inspire a change of heart.

Silicon Valley,this name conjures up word and brand associations like high-tech, digital, Facebook, Google, venture capitalism, Stanford, Palo Alto, Cupertino, Infinite Loop, LinkedIn, Cisco, cloud, big data,and Xerox PARC.

But think about the name in two parts. Firstly, silicon - the raw material for most commercial semiconductors, the backbone of the digital world. Next, valley - a physical description of a geological depression with predominant extent in one direction. Put the two words together and we have the metonym for the US high-tech industry. This physical, analogue place has been driving digital innovation and the creation of cyberspace for decades. There is a certain irony in this. One of the promises of digital innovation is that we can increasingly interact in digital cyberspace via globally diversified teams, that we can collaborate across time zones, and that we can video conference with partners and clients. Yet the history of digital innovation is one that has been consistently emerging from a specific geographical location - Silicon Valley. This ecosystem has been the central playground for digital ideas, and the mecca for innovators and venture capitalists since the name made its way into popular jargon in the 1980s.

While the valley reminds me of a large business park, its cafes, campuses and educational institutions speak to the history of innovation, and provide the habitat where digital ideas can flourish. It's immersive, it's an eco-chamber, it's incestuous, and it's highly analogue. Why? Trust, introductions, physical demos, handshakes, morning bike rides, children in the same school, serendipity, hype, constant pitching, caffeinated idea exchanges, Stanford alumni, MBAs. This analogue stuff matters - particularly when it comes to digital innovation.

In his book, Who's Your City?, Richard Florida shows maps of population growth, economic activity, innovation (as demonstrated by patent registration) and scientific discovery (as demonstrated by residence of the most heavily cited scientists). Silicon Valley is one of the top talent clusters, or ‘spiky' regions, in the world - a world which, according to Florida, is far from ‘flat'. Instead, geographical spikes are created by talented individuals who tend to cluster with one another, creating a (non-linear) multiplier effect that attracts additional talented individuals to that geographical area. This is certainly true of Silicon Valley.

- In 2006, the Wall Street Journal found that 12 of the 20 most inventive towns in America were in California, and 10 of those we in Silicon Valley. San Jose led the list with 3867 utility patents filed in 2005, and number two was Sunnyvale at 1881 utility patents.

- Silicon Valley has the highest concentration of high-tech workers of any metropolitan, with 285.9 out of every 1000 private-sector workers.

- Over 34 percent of Silicon Valley residents belong to the Creative Class - a key driving force for economic development in post-industrial societies - and the professional purpose of the class is ‘problem solving, [and] their work may entail problem finding' as well as drawing on ‘complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems using higher degrees of education to do so'.

- Real annualised house price growth in the area between 1950 and 2000 was the highest in the United States at 3.53 per cent, where the national US average was 1.7 per cent.

- Over 40 per cent of people in Silicon Valley have a Bachelor's degree or higher economic degree.

So what's the big takeaway from Silicon Valley's success? Increases in economic growth are only possible through innovation and innovation has a very simple source: new ideas. The success of Silicon Valley illustrates that face-to-face, informal, analogue networks that facilitate competition, team-work and the sharing of ideas are an essential part of cultivating innovation. In this region, analogue location has been driving digital innovation for decades. For policy-makers, creating physical clusters of talent at the firm, city or even regional level can spur innovation and unlock growth.

We identified a number of ecosystem enablers which helped drive Silicon Valley forward into one of the most successful talent clusters ever formed.

Although many advocate a "bottom up" approach to nurturing talent clusters such as Michael Arrington, in his article "Here's How The Government Can Fix Silicon Valley: Leave it Alone", few successful talent clusters have succeeded with minimal government intervention. Take the case of Silicon Valley, which traces it roots back to the development of military funded research in World War II. Government support continues to play a fundamental role in the development of Silicon Valley mainly through federal investment in universities, and by supporting the development of cutting-edge new technologies that have set the stage for many of the most innovative start-ups to come through Silicon Valley. Policymakers should aim to achieve the ‘sweet spot' in terms of both type and scale of government support.

Within Silicon Valley, there can be a sense of ruthless "no holds barred" competition, however, there's also an attitude of cooperation and an informal culture of networks that binds firms, people, ideas, capital and technology together. "Coopetition" is popular strategy predominant in Silicon Valley. What results is a high degree of cross-fertilisation and innovation, across organisational borders. In a recent Accenture survey, Silicon Valley employees were found to be 12% more willing to help somebody in their peer network compared to IT employees elsewhere, even if it was against their company's interest. Silicon Valley employees were also 11.4% more likely to choose their job because of the people they were working with. Co-workers are more of a deciding factor in employment decisions for IT professionals in Silicon Valley than elsewhere.

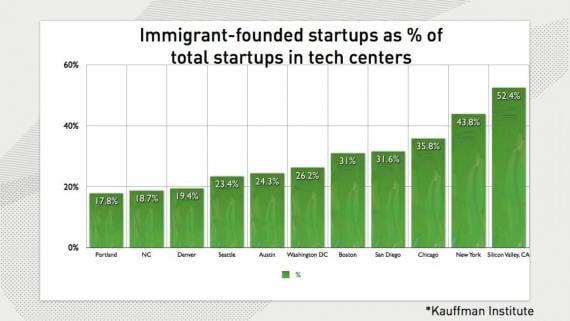

Attracting skilled foreign talent has been a key driver of Silicon Valley success. In a 2007 survey by Inc.com, first-generation immigrants were found to be on the founding teams of roughly 52% of all tech companies in Silicon Valley. Similarly, according to the Kauffman Institute, rougly 25% of US based science and technology companies founded from 1995 to 2005 had a foreign-born chief executive or lead technologist. As research shows that skilled immigrants are more likely to be entrepreneurial in nature, and in many cases, serial entrepreneurs, attracting skilled foreign migrants will be a key differetiator for innovation hubs of the future.

According to recent research by Shikhar Ghosh, a senior lecturer at Harvard Business School, about 75 percent of venture backed firms in the U.S. don't return investors' capital putting the failure rate well above previous estimates. Despite this high failure rate, compared to the global average of all startup ecosystems, Silicon Valley has 35% more serial entrepreneurs, that is, entrepreneurs who continuously start new businesses. And this serial entrepreneurism pays off. In a recent Harvard Business School working paper, Gompers, Kovner, Lerner and Scharfstein find evidence of performance persistence in entrepreneurship.

By contrast, first-time entrepreneurs have only an 18% chance of succeeding and entrepreneurs who previously failed have a 20% chance of succeeding.' Even serial entrepreneurs who have failed in the past have a slight advantage over first-time entrepreneurs when it comes to start-up success.

Another example of the importance of analogue location and human networks is the famous MBA - the Master of Business Administration. One of the business schools that consistently ranks in the top 10 internationally across the board is the Graduate School of Business at Stanford. In 2012, I had a chat with my Australian friend - I'll call him Matt - who is doing his two-year MBA at Stanford. I asked Matt about his main features and benefits of this exclusive program, which costs him around US $100,000 per year in tuition, books, medical insurance and a study trip. Matt responded, frankly, that was an insurance policy. ‘What?' I reacted. ‘Tell me more, Matt.' ‘Well you see, Anders', he said, ‘everyone here is already successful in their careers, and will be even more so going forward. Because of the glue and rapport we build, and the cognitive drills we have been through together, we will always help each other out. This means that if I ever lose a job or fail in my next start-up, I will simply call on one of my cohort mmbers and, at worst, they will give me a job - if not connect me with someone from their network who can help me out. This analogue glue that Matt, his mates, their predecessors and their successors have built up over generations of MBA graduates cements rapport, connection and reinvestment in local, digital ideas.

"Extract from Digilogue: how to win the digital minds and analogue hearts of tomorrow's customer by Anders Sorman-Nilsson"

The idea of innovation being spurred in talent clusters becomes more obvious when we move away from the idea of online networks and futuristic workplaces and onto old school networks formed around analogue locations. Long before the widespread adoption of telecommunications and social media, talented people have been flocking to, and flourishing in analogue networks. When they are encouraged, they become a hotbed of innovation.

(Source: Fast CoDesign)

Globoforce produces a great list of examples of groups of people within arts and culture who rose to prominence together just in the twentieth century: The Lost Generation, The Algonquin Round Table, The Bloomsbury Group, The Beat Generation, The Brill Building, Motown, The Silver Factory and the Cambridge Footlights Club just to name a few. It's no surprise that many of these people were rubbing shoulders long before their rise to stardom.

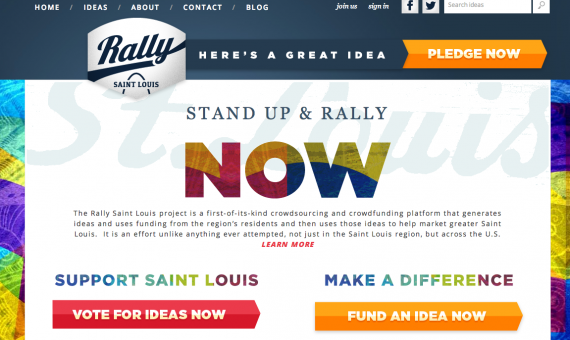

Cities ahead of the curve have already recognised the growing need to attract Millennial talent. For example, the city of Niagara Falls pays the student loans of students who will move to certain areas for work. St. Louis has created a crowdfunding platform giving young people a chance to generate ideas to improve the city called ‘Rally St. Louis'. In 2009, the Millennial Mayors Congress was created in Detroit which aims to improve the city' in various aspects to better attract Millennials. Numerous cities have made substantial developments in housing, nightlife, arts and culture, and employment as part of their growing efforts to attract young talent.

Given that the war for talent is likely to accelerate in the upcoming decade, the need for cities to become proactive in fostering clusters of innovation has never been greater. Creating the right conditions conducive to fostering innovation leads to a inflow of talent, which leads to a higher level of creativity and innovation, in turn, leading to a higher level of inward talent migration, creating a positive snowball effect of growth.

Header Text

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Header Text

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Header Text

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

& STAY UP TO DATE WITH FORESIGHTS AND TREND REPORTS!

WE WILL EQUIP YOU WITH THE VIDEOS AND MATERIALS YOU NEED TO SUCCESSFULLY PITCH ASN.

0 Comment